by G.R. Duxbury

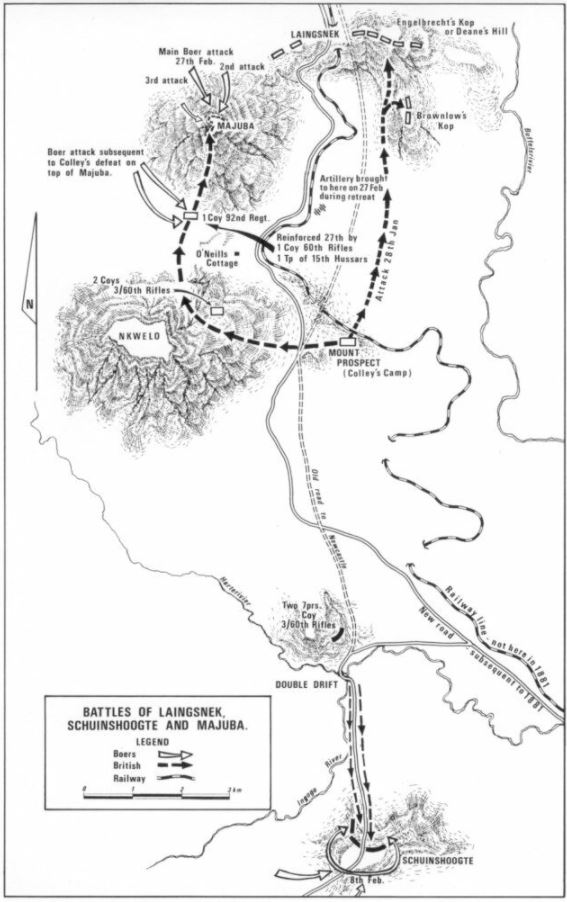

Colley suffered two crushing defeats at Laingsnek and Schuinshoogte. The second would have been avoided had he withdrawn to Newcastle to await reinforcements after the Laingsnek disaster but no doubt he weighed up the effect of such a withdrawal on the morale, not only of his own troops, but also on that of the besieged garrisons in the Transvaal, and decided that this would outweigh any advantages the move would give him. There might also have been the slight hope that the Boers would attack his camp and that this would be another ‘Ulundi’ and end once and for all the show of bravado that had carried the Boers thus far.

It would also appear from his various writings that he was still convinced that the Boer effort to this time was merely a ‘flash in the pan’.

When the action at Schuinshoogte took place the following troops were on their way to join Colley:

- 15th Hussars;

- 2/60th Rifles;

- 92nd (Gordon Highlanders);

- Contingent of the Naval Brigade and two guns. They arrived in Newcastle shortly after the battle of Schuinshoogte.

Meanwhile Sir Evelyn Wood, whose previous campaigning in South Africa had earned for him a reputation as a general of considerable ability, had accepted an appointment as Colley’s second-in-command, although he was senior to Colley and far more experienced.

Colley planned as phase one of his operations to form a second column at Newcastle under the command of Wood as soon as further reinforcements arrived. Phase two was the advance on Pretoria leaving Wood in command of all the troops in Natal. Phase three provided for Wood to move into the Transvaal as soon as Colley crossed the Vaal River at Standerton, Wood was then to take command of all troops east of the Vaal, including Newcastle, but would relinquish command of the remainder of the troops in Natal. Wood was to relieve Wakkerstroom and Lydenburg, whilst Bellairs at Pretoria would proceed to relieve Potchefstroom and Rustenburg. These details were set out by Colley in a letter to Sir Evelyn Wood, dated 4 February 1881. Colley also wrote as follows, ‘… I would gladly give you the Pretoria column, but I must push on there myself to assume the government, and the force is hardly large enough for two generals when all the rest of the command is left without one; the more so as there will be three generals when we reach Pretoria, as Bellairs has been given rank of brigadier-general. You will also, I am sure, understand that I mean to take the Nek myself!'(1)

The important aspect of this letter is the last sentence – Colley’s determination to have the honour of personally defeating the Boers at Laingsnek.

Was Colley’s next move – a move that appears to have been made in great haste, especially in view of the fact that only a few of the expected reinforcements had arrived (in fact these reinforcements could really be considered merely as replacements for the heavy losses to his force to date) – made so that he could claim a military victory instead of a politically inspired negotiated settlement? There had always been opposition in Britain to the Government’s annexation of the Transvaal and this opposition became stronger with the outbreak of the war, and increasingly so with each successive defeat. There was also growing support in the Cape for the Republic.

Negotiations had been entered into by Downing Street with President Brand (Orange Free State) since early January when he had been informed that ‘… provided only that the Boers will desist from their armed opposition to the Queen’s authority, Her Majesty’s Government do not despair of making a satisfactory arrangement.'(2)

Subsequent to the Battle of Laingsnek the British became aware that Burghers of the Orange Free State were moving on Newcastle to join the Transvaalers. Colley telegraphed President Brand in this connection. Brand in his reply denied the movement. He also ‘implored’ Colley ‘to prevent further bloodshed’. More interesting from Colley’s point of view was a reference by Brand to telegrams sent by Lord Kimberley aimed at bringing about an amicable end to the war.(3)

Further communication between Colley and Sir Hercules Robinson (mediator between Lord Kimberley and President Brand) on the one hand and between Colley and Brand on the other in regard to the peace proposals to date, about which Colley had not been informed, followed.

On 5 February Colley telegraphed Lord Kimberley as follows:

‘Have received two long telegrams from Brand earnestly urging that I should communicate your reply to him to Boers, state nature of scheme, and guarantee their not being treated as rebels if they submit. I have replied that I can give no such assurance, and can add nothing to your words, but suggested he may do good by making your reply known through Transvaal.'(4)

There is no doubt when reading the numerous telegrams that passed to and fro that the British Government still thought grandly of its ability to inflict defeat on the Transvaal and that despite three major defeats at the hands of the Transvaalers it intended giving away no advantages in advance – the victorious Boers were expected to lay down their arms and thus give Colley and his forces, rapidly being reinforced, free entry to the Capital.

On this question of ‘submission and a satisfactory arrangement’, i.e., reasonable guarantees as to the treatment of the Boers, Colley addressed a letter to Lord Kimberley on 12 February ‘… I imagine the question will be what your Lordship means by “reasonable guarantees” for their treatment. I take it the Boer leaders will not submit unless they are assured they will not be singled out for punishment, and on the other hand I imagine that no settlement of the Transvaal can be safe or permanent which leaves them there as the recognised and successful leaders of the revolt…'(5)

The first tangible result of the protracted negotiations arrived in the form of a letter from the Triumvirate to Colley dated 12 February 1881. It read:

YOUR EXCELLENCY, – Having arrived here at headquarters, and having examined the several positions taken by the Honourable P.J. Joubert, Commandant-General of the Burghers of the South African Republic, I have found that we are compelled against our will to proceed in a bloody combat, and that our positions as taken are of that nature that we cannot cease to persevere in the way of self-defence as once adopted by us so far as our God will give us strength to do so.

Your Excellency, we know that all our intentions, letters, or whatever else, have failed to attain the true object because they have been erroneously represented and wrongly understood by the Government of the people of England. It is for this reason that we fear to forward to your Excellency these lines. But, your Excellency, I should not be able to be answerable before my God if I did not attempt once more to make known to your Excellency our meaning, knowing that it is in your power to enable us to withdraw from the positions taken up by us. The people have repeatedly declared their will, upon the cancellation of the Act of Annexation, to co-operate with Her Majesty’s Government in everything which can tend to the welfare of South Africa. Unhappily the people were not in a position to accomplish their good intentions, because they were unlawfully attacked and forced to self-defence. We do not wish to seek a quarrel with the Imperial Government, but cannot do otherwise than offer our last drop of blood for our just rights, as every Englishman would do. We know that the noble English nation, when once truth and justice reach them, will stand on our side. We are so firmly assured of this that we should not hesitate to submit to a Royal Commission of Inquiry, who we know will place us in our just rights; and, therefore, we are prepared, whenever your Excellency commands that Her Majesty’s troops be immediately withdrawn from our country, to allow them to retire with all honours, and we ourselves will leave the positions as taken up by us. Should, however, the annexation be persevered in, and the spilling of blood be proceeded with by you, we, subject to the will of God, will bow to our fate, and to the last man combat against the injustice and violence done to us, and throw entirely on your shoulders the responsibility of all the miseries which will befall this country.(6)

One cannot understand how the British could be so naive as to expect thc Boers to lay down their arms and submit; the Boers having done their utmost to reach a peaceful settlement and re-instate their Republic and, when this failed, having resorted to the almost unbelievable – the taking up of arms against the mighty Lion and, having done so, then inflicting upon the mighty Lion three serious wounds besides bottling up all his garrisons in the Transvaal so that they were now helpless to move out against the so-called ‘Rebels’. The Boers had nothing to lose but everything to gain. In poker parlance they held all the cards and yet the enemy was calling the bets.

On 16 February Kimberley authorized Colley to agree to a suspension of hostilities if the Boers desisted from further armed opposition.

The thought of peaceful negotiation appears to have worried Colley. A letter from him to Wolseley on 21 February bears this out, ‘… I am daily expecting to find ourselves negotiating with the “Triumvirate” as the acknowledged rulers of a victorious people; in which case my failure at Laing’s Nek will have inflicted a deep and permanent injury on the British name and power in South Africa which it is not pleasant to contemplate.'(7)

There seems no doubt whatsoever that Colley at last saw the road to success opening before him – but also visualized that before he could bring about a glorious victory the ‘peace-at-any-price folk’ would deprive him thereof.

It would seem that his next move was made hastily and without discussing the matter with his staff or the commanding officers of the regiments under his command.

He had been joined at Mount Prospect by the 92nd Gordon Highlanders, about 50 Naval Brigade, with two guns, and a troop of 15th Hussars. The remainder of the Hussars and the 2/60th Rifle Regiment remained at Newcastle ready to join a general attack.

The 92nd had arrived from a successful campaign in Afghanistan – bronzed, fit, and wearing khaki with, of course, their well-known tartan kilts. They also wore khaki covers for their white helmets and the officers were all equipped with the newest addition to their accoutrements – the Sam Browne belt, only recently introduced in India for the first time and not used before in South Africa.

On 21 February, Colley, following on the authority vested in him by Lord Kimberley, wrote as follows to Vice-President Kruger:

‘… I am to inform you that on the Boers now in arms against Her Majesty’s authority ceasing armed opposition, Her Majesty’s Government will be ready to appoint a Commission with large powers who may develop the scheme referred to in Lord Kimberley’s telegram of the 8th inst. communicated to you through his Honour, President Brand.

I am to add that upon this proposal being accepted within forty-eight hours, I have authority to agree to a suspension of hostilities on our part.'(8)

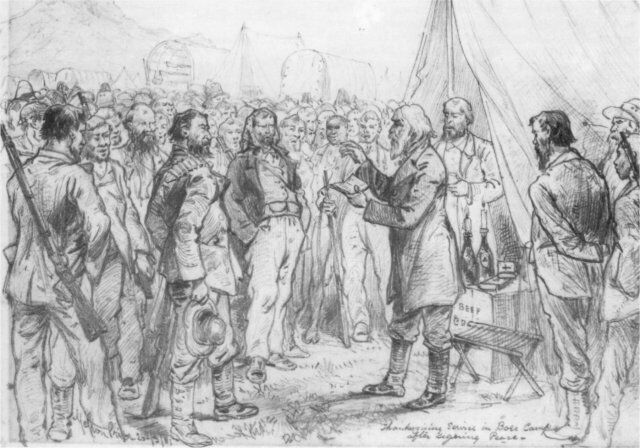

By kind permission of the National Cultural History and Open-Air Museum, Pretoria.

Commandant Smit received the letter at Laingsnek on 24 February and despatched it to Kruger at Heidelberg by mounted messenger. There was no way that the messenger could reach Kruger in less than two days so it is unlikely that Kruger received it before 27 February. It is obvious from this that the letter was a token to please his superiors and that Colley had no real intention of adhering to the suggested suspension of hostilities, for in the evening of Saturday, 26 February 1881 he finally made up his mind to march on Majuba, his action ostensibly based on the fact that the ultimatum had expired, whereas he must have been fully aware that there was no way in which Kruger could have received his letter, considered the contents, and replied to reach Colley between 21st and 26th February.

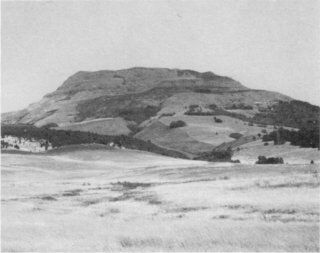

There are many questions that require answering when considering the happenings of the 26th and 27th. The first is Colley’s reason for occupying the summit of this mountain which stands some 600 m above Mount Prospect, the site of his camp. Admittedly it has an excellent view of Laingsnek and Colley would thus be able to see clearly the Boer defences. But in actual fact he knew perfectly well what those defences consisted of, and a few scouts could have brought him right up to date. No, there must have been another reason. He would also have had a commanding view of the Boer laagers but two, perhaps all three, were out of rifle range and what good could a commanding view do him? It had to be something else. He did not take artillery to the top of the mountain and it is doubtful that he could have done so – the 9-prs were too heavy. Perhaps with a great deal of effort he might have dragged up the two 7-pr mountain guns but the route he took made this an extremely difficult undertaking. Assuming that he had succeeded in so doing what of the problems of ammunition? A bombardment without an infantry follow-up would have been useless. Some of his officers and men, writing many years later stated that on the morning following the night ascent they fully expected to see the guns move close to Laingsnek, whereafter Colley would have directed their fire on to the nek which would then have been attacked by the troops left in camp, hopefully reinforced during the night by the newcomers still in Newcastle. Such statements do not make sense. There was no fire-drill in 1881 that made possible the control of fire from a distance. Artillery fire in 1881 was still direct, over open sights.

The Gatlings were also too heavy and cumbersome to manhandle up the mountain. This leaves only the three rocket tubes which could have been taken up but they did not have the range to one laager and, as with the 7-prs, what would have been the use of a few rockets aimed at the laagers and/or nearest trenches at Laingsnek without an infantry follow-up? The use of artillery was obviously discounted in Colley’s plans. He must, therefore, have decided on an entirely infantry role. But what? Occupying the summit would certainly not get him into the Transvaal. In fact the Boers might easily have attacked his camp at Mount Prospect whilst he was sitting on Majuba and, having eliminated the very much reduced force in the camp, invested Colley on his mountain fortress. Colley could of course have made a descent on the Boer side of Majuba but his troops would have been sitting ducks as they negotiated their way down even this comparatively easy route, but this would not have helped him because the Boers were strongly entrenched at Laingsnek and to get to the Transvaal he had to capture and open the nek for his wagon-trains to pass through. Without their transport the troops were helpless except for short marches.

Military leaders and historians have argued the pros and cons of Colley’s actions in occupying Majuba for the past 100 years without reaching a sound conclusion. It is my belief that Colley had no sound plan. Had he had one he would surely have discussed it with his second-in-command or some other officer of his staff but all evidence says that he did not. I am of the further belief that his sole intention was to make a show of troops on this ‘unassailable’ feature. That in his opinion the Boers would be taken by surprise at his feat, in fact staggered at the immensity of his night achievement and, without waiting to analyse what could be done about it, inspan their wagons, mount their horses and depart for their farms as quickly as they could. What else? Here would be the military victory he so much hoped to achieve and, even better, a personal victory; a bloodless military settlement of the war that would vindicate his previous defeats and the great loss of lives which must, from all accounts, have weighed heavily on his mind.

One other odd aspect is that knowing of the reinforcements, some of which had reached him, others at most a few days march distant, why did he not decide to have another go at taking the nek?

Colley had long known that the Boers had an outpost on top of Majuba during the day. Native spies informed him that this picquet withdrew at night. This knowledge might possibly have sown the seeds which blossomed into his final decision to occupy the mountain but his plans did not go as far as surprising the picquet when they arrived – in fact all his actions made quite certain that by 08h00 every Boer in the area knew of his occupation of the summit.

Colley decided against detailing one of his infantry battalions for the task. Instead he formed a composite force under his personal command, with Colonel Stewart, of the 3rd King’s Dragoon Guards, as his Chief-of-Staff. The force consisted of two companies 58th Regiment (170), two companies 3/60th Rifles (140), three companies 92nd (Gordon Highlanders) (180), and one company Royal Naval Brigade (64) – in all about 554 riflemen. How much better it would have been had he given the task to one of the infantry battalions and told the commanding officer to get on with the job. Both the 58th and the 3/60th were thirsting for revenge after their defeats, respectively, at Laingsnek and Schuinshoogte. The 92nd, freshly arrived from the Afghan Campaign and battle tried would obviously have been a good choice.

The force assembled in camp with barely three hours warning and set out under cover of darkness at 21h30 on Saturday, 26 February 1881. Its route took it from the camp at Mount Prospect up the south eastern slopes of the Nkwelo (sometimes spelt Inkwelo or Imquela) Mountain, along a connecting ridge to the south side of Majuba, and up the very steep last few hundred metres. Such a climb would not have been easy even in the daytime laden as the men were. Historians have claimed that to attempt it at night maintaining silence and without the use of lights was expecting too much of his men. The route rendered it extremely difficult for even the most observant Boer scout to see the movement as an approach march to the summit of Majuba, and to make doubly certain they were not seen no lights were carried and the troops ordered to move as silently as possible.

Although the force that started out was about 554 strong, first the 60th Rifles were dropped en route on a shoulder of the Nkwelo and one company of the 92nd was deployed on the ridge connecting Nkwelo and Majuba almost directly above O’Neill’s cottage (where the peace was subsequently negotiated and which today still stands as a national historical monument). The total force, which reached the top of the mountain, was therefore approximately 365/375 or about half a battalion strong.

The first troops breasted the summit between 03h00 and 04h00 on Sunday morning. Historians relate that ‘…. the men, exhausted, kept throwing themselves to the ground but were directed by the General himself to move out to the perimeter’ and ‘…. the climb in itself had been bad enough but when the load of approximately 58 lbs carried by each man is taken into consideration it must have been formidable.’ They each carried a rifle, bayonet and 70 rounds of ammunition, a greatcoat, blanket, waterproof sheet, waterbottle and 3-days rations. In addition a liberal number of entrenching tools were distributed to each company. It is nevertheless interesting to note that Lieutenant Ian Hamilton (later General Sir Ian Hamilton, GCB, GCMG, DSO, TD) shortly after the battle wrote ‘… the men were too excited to feel fatigue and I saw no signs of it.’

In order to find out for myself I decided to repeat Colley’s night march. This was done on the night of 11 April 1968. My party consisted of eight. Ages ranged from 24 to 50. We were dressed in replicas of the uniforms of the 58th Regiment which had been made for the film ‘Majuba’ which was being filmed at the time. The one exception was our boots which, for comfort, were old and worn-in and not strictly according to the pattern of 1881. Our clothing and equipment weighed 58 lbs.

We set out from the site of Colley’s Camp near the present Mount Prospect Cemetery at 21h30. The night was extremely cold with a heavy mist which grew in intensity as we made our way upwards. Light rain fell from 23h00. We were thus bitterly cold and thoroughly wet for most of our journey.

We were delighted when we came across the positions occupied and entrenched by the 3/60th Rifles on the east shoulder of Nkwelo Mountain. Although the shallow trenches were overgrown they could easily be identified as platoon and company positions.

After leaving the shoulder our route took us along the heavily wooded ridge connecting Nkwelo and Majuba. Except for the dense woods the route remains very much as it was during Colley’s march.

From Mount Prospect Camp to the top of Majuba via Nkwelo is approximately 8 km. We timed our arrival on top for 03h00 – an average of approximately 1,5 km per hour. As things turned out we could quite easily have breasted the top before midnight had we desired but this would not have proved what we set out to prove.

It took us ten minutes to recover from the last few hundred metres which proved quite strenuous and steep compared with anything encountered on the early part of the route.

We then attempted to sleep but this was difficult and uncomfortable owing to the cold and our wet clothes. Reveille was at 05h30. By this time all members of the party were completely refreshed. Everyone in the party was fit to do battle.

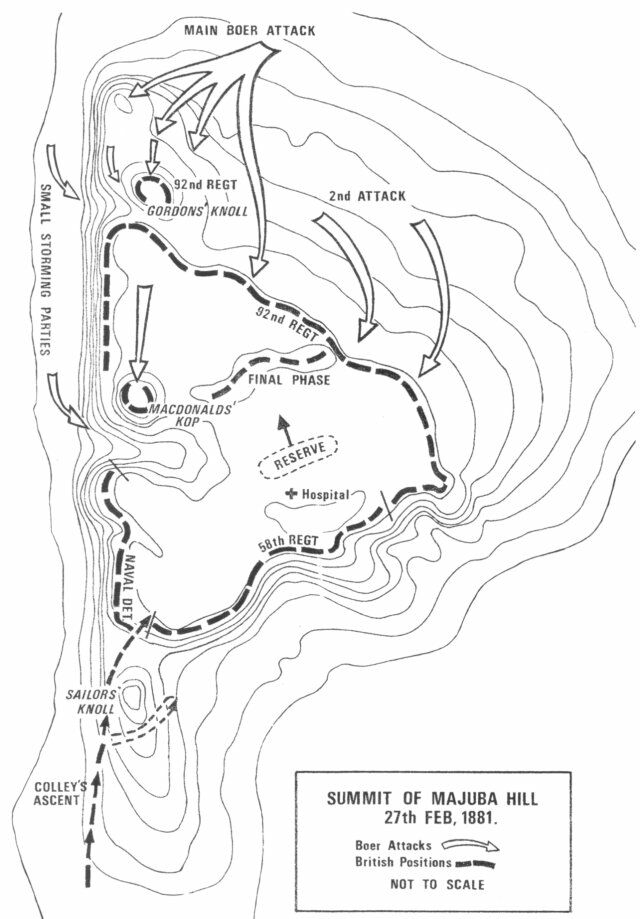

The top of Majuba is hollowed out like a saucer. On the west towards the southernmost point is a large gully. A fold and rocky ridge rise out of the centre of the hollow. On the west is a prominent point known as MacDonald’s Koppie and at the north-western extremity of the hill, in fact a little beyond the top, is an isolated knoll which is now known as Gordons’ Knoll. On the north and east of this Knoll there are a series of terraces or large steps up which the Boers pressed their attack.

Attempts were made to post the men in their respective companies on the perimeter. If every rifleman had been posted on the three-quarter mile perimeter the maximum density would have been one rifle to every four metres. This was not done as Headquarters and about 110 men from all units, as well as the hospital and commissariat, were positioned in the central depression. Here a shallow well was dug for water which seems to indicate that Colley intended a stay of some duration. Water was struck at a depth of about 1,5 m.

No cover of consequence was erected and no breastworks worthy of mention, except a few built by the Naval detachment, were prepared. This is difficult to understand because 80 picks and 80 spades were carried up the steep mountainside.

Some of the men were instructed to collect piles of stones which would afford them cover in the event of an attack, but generally no serious attempt appears to have been made in this direction. Likewise no attempt at a serious reconnaissance was carried out – had there been there is no doubt that the extensive dead ground over which the Boers attacked would have been covered.

The first streaks of dawn showed the occupiers of Majuba that the Boer camps in the north and behind Laingsnek were astir with lights in many of the tents and wagons. Away to the right could be seen the Boer left flank positions where the Mounted Squadron had suffered a repulse on 28 January. It was recorded in several diaries of the time and shortly afterwards as a ‘thrilling sight’.

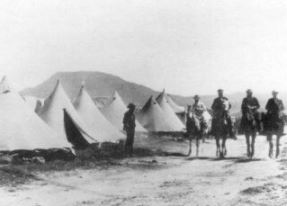

One of three Boer laagers Majuba can be seen in the background.

By courtesy Local History Museum, Durban.

Colley’s men expected big things to happen and were excited. The Boers were certainly at their mercy, or at least so they thought, but they had badly under-estimated the quality of their opponents. It apparently never occurred to the British to remain quietly hidden and to surprise the Boer patrol that occupied the hilltop by day. Instead the troops exposed their occupation by walking on the skyline and even hurling insults and waving their fists and rifles at the Boer positions. Some shots were fired at a passing Boer patrol and this appeared to stir the Boer camp to great activity.

As soon as Joubert became aware of what had happened he entrusted the task of ejecting Colley’s force to Commandant N.J. Smit. The records do not clearly state the exact composition of his force. Some sources say that the task was given to Commandant D.J. Malan. It would appear to me that Smit was in overall command but that the very nature of the Boer plan called for a three-pronged attack and that Malan, Pretorius, Meijer, Roos, and Ferreira, and perhaps others unnamed, played vital roles in each of the attacks. Smit knew the ground well and from previous encounters with the British was not a bit worried about the quality of his opponent’s marksmanship. His plan was simple – to build up a strong firing line about 150 metres from the summit where he could shoot it out. He lost no time, for as soon as he had gathered a small force he commenced the ascent.

He had good cover in his advance to the lower slopes and his way was not blocked by outposts or patrols. It is once again difficult to estimate the strength of the Boer forces but a great deal of research has left me with a firm impression that the Boer force at no time exceeded 350 – nothing like the figure of 1 000 or more, often quoted.

Taking full advantage of the cover afforded by sparse scrub and dead ground formed by the series of terraces, the Boers carried out a methodical attack – a perfect example of fire and movement as taught even today, except that their supporting fire was from rifles and not flanking machine-guns as it would be in modern warfare. In the initial stages only a small group of the 92nd (Gordon Highlanders) got in Smit’s line of advance. This small group had gone too far forward in the pre-dawn and occupied the first slopes between the crest and what became known as Gordons’ Knoll. The Boers collected behind this Knoll on which were posted a mere two or three men and from this position they proceeded to shoot anyone who showed himself either on the Knoll or on the skyline. Having decimated the defenders of the knoll, the Boers rushed the summit where they were engaged by about 20 men of the 92nd who had been posted on MacDonald’s Koppie, so named after Lieutenant Hector MacDonald who was one of the few survivors of this little group. (He went on to a distinguished career and succeeded General Wauchope as commander of the Highland Brigade at Magersfontein in 1900.)

With this turn of events the remainder of the troops left the perimeter and gathered like sheep behind the low ridge in the centre directly in the path of the advancing Boers. Great efforts were made by the officers to rally their men and get them back to their positions. Every effort was made to rush reinforcements to aid the Highlanders who were bearing the brunt of the attack at this stage. Whilst the men obeyed, some of them did so with the utmost reluctance which made it necessary for the officers to coax them and there were many commands to move up. It was a mixed reserve consisting of 92nd, 58th, and Bluejackets. Lieutenant Hamilton later wrote, ‘I never saw such a mob as this reinforcement.. . Some were properly dressed, others were without helmets, coats or belts. The whole formed a sort of mixed crowd being led on by their officers. I fancy they were considerably startled by being so suddenly hurried up, many of them out of a sound sleep. Anyway, I did not like the way they came on. As they approached the place where my men had been, they opened a heavy fire, though I don’t quite think they saw what they were firing at. The Boers, however, did not apparently much like the whistling of the bullets, and they drew back behind the crest of the knoll.'(9) There was a distinct lull in the firing at which stage the officers attempted to separate and re-group their men. The Boers were of course also re-grouping so as to be able to give supporting fire without hitting their own men and distributing ammunition to those who had been most heavily occupied in giving covering fire.

This might have been the opportunity for the British to restore the position with a bayonet charge. However, the target presented by the massed troops was so great that the Boers again poured in a heavy fusillade. A great number of the reserve were immediately knocked down and the balance rushed headlong back into the dip. Hamilton, now wounded, ran down to General Colley and saluting said: ‘I do hope, General, you will let us have a charge, and that you will not think it presumptuous on my part to have come up and asked you.’ To which Colley replied: ‘No presumption, Mr Hamilton, but we will wait until the Boers advance on us, and then give them a volley and charge.'(10) It is on record that other appeals were made but to all the General returned non-committal replies.

In the meantime the Boers had quietly slipped around under cover of the crest-line to the right of the British and soon were pouring heavy fire into their backs at almost point-blank range. A fresh body of Boers now threatened the left-front flank and things got out of hand. Discipline was fast on the wane but what could be expected when the men belonged to three different regiments and the personal influence of their officers was missing? It was not long before the defence wavered and finally broke with a wild rush into the basin and up the slope to the south-east perimeter. Hamilton described the bullets as pitting on the ground like hailstones. Many of the men who reached the perimeter flung themselves wildly over its precipitous edge. Some paused long enough to see the sheer drop and attempted to veer round to the south but few covered the fifty or seventy metres without being hit.

General Colley made a move in the direction of his broken and fleeing force, shouting out, it was later reported by several survivors, ‘Steady and hold the ridge.’ It was at about this time, 13h00, that General Colley fell mortally wounded. Several Boers have claimed to have shot him. One old veteran in 1949 stated that with Commandant Joachim Ferreira, Stefanus Roos, and Gideon Erasmus, he breasted the crest of the mountain ahead of a party of Boers. They saw a man standing about 200 metres away and three of them fired simultaneously. The man fell. When they reached the body they found they had shot General George Colley. He also informed the writer that for years until the ascent became too much for him, he climbed the mountain on the anniversary of Colley’s death and laid flowers on the spot. One J.J. van Tonder, who was one of the storming party, wrote, ‘Toe dit nou klaar was loop ek die 10 tot 12 tree na die Goeverneur, waarbij daar nou alreeds twee burgers en ‘n Hotnot staan. Toe ek bij die Goeverneur kom neem ek sij helm bij die pen, en lig dit van sij gesig… Colley was dood. Die koel het deur die helm en bo die regteroog ingegaan en agter die linker oor uitgekom. Ons was die dag onder bevel van Gen. Joachim Ferreira.’

Several eye-witnesses who examined the body stated positively that Colley was killed by a single bullet through the head, apparently at very short range and that there were no other injuries except slight abrasions from the climb and his fall on being shot. These statements are confirmed by medical evidence prior to the burial. If, in fact, Colley fell as the result of the simultaneous fire of the trio mentioned above the honour of killing in battle the enemy Commander, who was also Governor of Natal, must be shared by the group. However, this version does not agree with the many versions of the shot being at short, almost point-blank range, perhaps as little as 5 to 10 paces. However those who put forward this theory may have forgotten the devastating effect of the bullets in use at the time and attributed the enormous hole at the back of his head to the short range. The historian Froude went as far as to put forward the theory of a self-inflicted wound.

No one can say for certain.

Smit had carried out what 60 years later in World War II would have been termed a perfect text book infantry assault.

When Colley fell the Battle of Majuba was almost over. Sporadic fire continued whilst the Boers picked off fleeing men as they appeared on the slopes below. Many were rounded up as they hid behind bushes and rocks in the hope that they would be able to make their way safely back to camp under cover of darkness.

There were still the two groups Colley had left on the ridge between Majuba and Nkwelo and the Boers were not long in putting in an attack on the position nearest Majuba. This was the position held by the Company of the 92nd under Captain Robertson. It had been reinforced during the morning by a company of the 60th Rifles and a troop of 15th Hussars. Before becoming fully committed to battle, this force was ordered to withdraw and in so doing lost four killed, eleven wounded and twenty-two prisoners. The two companies left on Nkwelo Mountain were not engaged by the Boers and silently withdrew to Mount Prospect Camp without attempting to assist either Colley’s or Robertson’s forces. Neither group had been given orders by Colley as to what was expected of them should they be attacked.

The British losses on this fateful day were 92 killed, 134 wounded, of whom a few succumbed during the following few weeks, and 59 taken prisoner.

The Boers lost 1 killed and five wounded. One of the five subsequently died from his injuries.

By courtesy Local History Museum, Durban.

Much has been written about the defence put up by the British on Majuba and in particular the magnificent effort of the 92nd. However, no more damning evidence of their failure, as well as that of the other regiments engaged, could be found than in the Boer casualty list.

Many excuses have been put forward by the British for their defeat. One such was that the men were too tired after their strenuous climb but this was refuted by Hamilton who was present and our subsequent climb. Another is that they ran out of ammunition – since refuted by numerous persons who were present. Most ammunition pouches were at least half full at the end of the battle. That the Boer tactics using fire and movement took them unaware is certain. What the British assumed was idle fire at the grass-tops was in fact covering fire for the Boers who were crossing the terraces and climbing exposed portions of the slopes. That the British were inferior shots has often been proved and partly accounted for their defeat. Whatever is said there is no doubt in my mind that British courage failed at the crucial stage of the battle and that they turned and fled, otherwise why only one Boer killed? It is an admission that none would easily make but the casualties give the lie to claims of a gallant defence, etc., etc. Certainly there were heroic actions but these were in the minority. There was an award of the Victoria Cross to L/Cpl J.J. Farmer, Army Hospital Corps, but acts such as his were extremely rare. The defeat at Majuba was a sad blow to British prestige and in my opinion this is one of the most important factors to be considered in relation to the causes of the Second War of Independence of 1899-1902.

Some seventy-five NCOs and other ranks, and one officer, a Captain Maude of the Grenadier Guards, on temporary attachment to the 58th, were buried on the mountain top.

Colley’s body was carried by a party of British prisoners to the Boer Camp and after a few days it was handed over to the British for burial. It was interred in the cemetery at Mount Prospect Camp with those brought down from the mountain and alongside a number of those who had perished at Laingsnek and Schuinshoogte and, contrary to the general practice of the time, had been removed from the field of battle.

Needless to say the British were staggered by the defeat and death of Colley. Sir Evelyn Wood rushed to Mount Prospect, and Sir Frederick Roberts was appointed in Colley’s Command, but in actual fact the First War of Independence ended with Colley’s defeat at Majuba and Roberts did not assume active command.

On 6 March Evelyn Wood met Joubert at O’Neill’s Cottage, below Majuba, just off the present Durban- Johannesburg road, close to Laingsnek, where provisional peace terms were discussed. The negotiations were delayed and often heated. Paul Kruger joined the conference and held out for complete independence. The deadlock was only overcome when President Brand arrived and interceded. The terms of the truce of O’Neill’s Cottage were finally ratified in August 1881.

Thus ended the War of 1880-1881 but the freedom gained so nobly by the Burgher Forces was short-lived and ended with the defeat of the Republics in the Second War of Independence of 1899-1902 but despite defeat (this time by an army of close on half-a-million strong), the spirit born of the victory at Majuba lived on. To me it would seem to be this spirit above all else that spurred on a section of our community to regain South Africa’s independence – an ideal achieved in 1961.

References:

- Butler, Sir W.F., The Life of Sir George Pomeroy-Colley (John Murray, London, 1899), pp.295-296.

- Ibid, p.322.

- Ibid, p.326.

- Ibid, p.327-328.

- Ibid, p.330.

- Ibid, pp.330-331.

- Ibid, p.343.

- Ibid, p.344.

- Letter to Major R.J. Southey.

- Letter to Major R.J. Southey.

Acknowledgments.

Grateful thanks are recorded to the authors and/or compilers of the following books used for the series of articles entitled ‘Battle of Bronkhorstspruit’, ‘Battle of Laingsnek’, Battle of Schuinshoogte’, and ‘Battle of Majuba’.

- Bellairs, Lady, The Transvaal War, 1880-81 (William Blackwood, 1885).

- Bulpin, T.V. The Golden Republic (Howard B. Timmins, Cape Town, c. 1950).

- Butler, Sir William F. The Life of Sir George Pomeroy-Colley, 1835-1881 (John Murray, London, 1899)

- Cachet, Frans Lion, De Worstelstrijd der Transvalers (J.H. Kruyt, Amsterdam, 1882).

- Callwell, Sir Charles Edward, and Sir John Headlam, The History of the Royal Artillery. (Royal Artillery Institution, Woolwich, 1931-1940).

- Carter, T.F. A Narrative of the Boer War (Remington & Co. London. 1883).

- Clowes, Sir William Laird, etc. The Royal Navy. A history from the earliest times, etc. (Sampson, Low, Marston, London, 1897-1903).

- du Plessis, C.N.J. Uit de Geschiedenis van de Zuid-Afrikaansch Republiek en van de Afrikaanders (J.R. de Bussy, Pretoria, 1898).

- Gardyne, C.G., The Life of a Regiment: the History of the Gordon Highlanders (David Douglas, Edinburgh, 1901-03).

- Grant, James, Recent British Battles on Land and Sea (Cassell, London, 1897).

- Great Britain. Blue Books, of the period 1877-1881; Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, of the period 1881.

- Gurney. R., History of the Northamptonshire Regiment 1742-1934 (Gale and Polden, Aldershot, 1935).

- Hamilton, Sir Ian, The Commander, ed. by A. Farrar-Hockley (Hollis and Carter, London, 1957).

- Rolt, H.P., The Mounted Police of Natal (John Murray, London, 1913).

- Rume, JJ.F., A Narrative of the 94th Regiment in the Boer War, 1880-81.

- Jorissen, E.J.P., Onbekende herinneringe van Dr E.J.P. Jorissen oor die Eerste vryheidsoorlog (Wallach, Pretoria, reprint from ‘Die Volkstem’ 192?).

- Jourdain, H.F.N., The Connaught Rangers, Vols I and II (Royal United Services Institution, London, 1924-1928).

- Kemp, J.C.G., Vir Vryheid en vir reg (Nasionale Pers, Cape Town 1941).

- Klok, J., De Boeren-republieken in Zuid-Afrika, hun ontstaan, geschiedenis en vrjjheidsoorlogen (J. de Liefde, Utrecht, 190?).

- Natal Mercury, Durban, of the period.

- Newman, Charles L. Norris, With the Boers in the Transvaal and Orange Free State, 1880-1 (Wm. H. Allen & Co, London, 1882).

- Porter, W., History of the Corps of Royal Engineers (Longmans, London, 1889).

- Preller, Gustav Schoeman, Daglemier in Suid-Afrika (Wallachs. Pretoria, 1937).

- Ransford, Oliver, The Battle of Majuba Hill (John Murray, London, 1967).

- Reed, J.H., The Transvaal from Without (Sowler, Manchester, 1900).

- Ritchie, J.E., Imperialism in South Africa, 2nd Ed. revised (James Clarke & Co, London, 1881).

- Schoeman. J., Generaal Hendrik Schoeman – was hy ‘n verraaier? (Caxton, Pretoria, 1950).

- Southey, R.J., Numerous discussions, correspondence, and unpublished articles at S.A. National Museum of Military History, Johannesburg.

- Theal, G.McC., History of South Africa from 1873 to 1884 (George Allen and Unwin, London, 1919).

- Transvaal Government Gazettes (Pretoria, 1880 to 1881).

- Transvaal, De Staats Courant gedurende den Vrjjheidsoorlog van 1881 (J.F. Celliers, Pretoria, 1885).

- Tylden, G., A study in attack – Majula 27 February 1881 (In Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, London, Vol.39 No.157, March, 1961).

- Van Schoor M.C.E. Amajuba! – (A series of articles in ‘Die Taalgenoot’, 1962).

- Williams, Charles, The Life of Sir Henry Evelyn Wood (Sampson Low, London, 1892).

- Wilmot, Alexander, The History of our own times in South Africa (Juta, Cape Town, 1897-99).

- Wormser, J.A., Drie en zestigjaren in dienst der vrjjheid de levensgeschiedenis van Generaal Joubert (Höveker & Wormser, Pretoria, 1900).

This post/article was copied and taken from this page of the The South African Military History Society and used with their kind written permission. Thank you so much Joan Marsh!